Expect offsetting impacts of deregulation, lower tax rates, and tariffs—but also great uncertainty.

Assessments of the impacts of President-elect Trump’s economic policies are just as polarized as the political arguments of the recent campaign. Trump’s detractors provide deeply negative economic estimates of his policy statements on tariffs and immigration. The Trump camp sees only clear skies, stronger economic growth, and buoyed prosperity.

Drawing on the history of Trump’s first term, an evenhanded assessment of the four pillars of Trump’s current economic platform—higher tariffs and tough anti-China policies; extending the 2017 tax cuts; deregulation and increasing government efficiency; and deporting immigrants—suggests that there will be offsetting pluses and minuses. The net economic impacts are most likely somewhere in between the most pessimistic prognostications and the rosy scenario envisioned by the Trump team. There are many key uncertainties and risks.

Trump’s second presidential term will begin with the economy on a sound footing, with solid economic growth and healthy labor markets. Real GDP growth has remained resilient, concluding with 2.8 percent annualized growth in the fourth quarter of 2024, well above standard estimates of sustainable longer-run potential growth. The unemployment rate in November was 4.2 percent, close to standard estimates of full employment. Inflation has been sticky, remaining modestly above the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent longer-run target. The dollar has been strengthening.

The programmatic specifics of Trump’s economic proposals and the timeline for their implementation are not yet available, which limits the detail of this analysis. Most likely, the actual policies will be less severe than suggested by Trump’s blustery campaign platform. The economy is likely to experience continued expansion, probably with modestly slower growth, while inflation rises marginally. Disruptions stemming from Trump’s proposal to deport immigrants pose the biggest risk in the year to come.

Trump’s first term

Trump’s first presidential term provides valuable insight. The shift to deregulation—a decided about-face from the Obama presidency—and the 2017 tax cuts boosted confidence and economic activity, while the tariffs and trade war with China, beginning in mid-2018, harmed performance. Overall, the economy continued to grow while responding to these policy shifts. The exchange value of the US dollar initially appreciated in response to Trump’s election, then depreciated significantly through spring 2018, and subsequently appreciated when tariffs were imposed. Inflation decelerated after the imposition of tariffs, contrary to current concerns that tariffs are inflationary. The Fed gradually raised rates and normalized monetary policy in 2017–18, and lowered rates in 2019 as the economy weakened.

In a proposed deficit-neutral tax reform package put forward in early 2017, sizable cuts in individual and corporate tax rates were to be offset by revenue increases generated by a border tax. Lengthy congressional negotiations led to a dropping of the border tax provision and enactment of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 in December. This added significantly to deficits. It was widely criticized as unnecessary fiscal stimulus during a mature economic expansion that provided most benefits to higher-income taxpayers. Trump then began imposing tariffs in April 2018 and his trade war with China began in July. Tariffs were imposed on approximately $380 billion of imported goods, the bulk of which were from China. The Biden administration extended those tariffs.

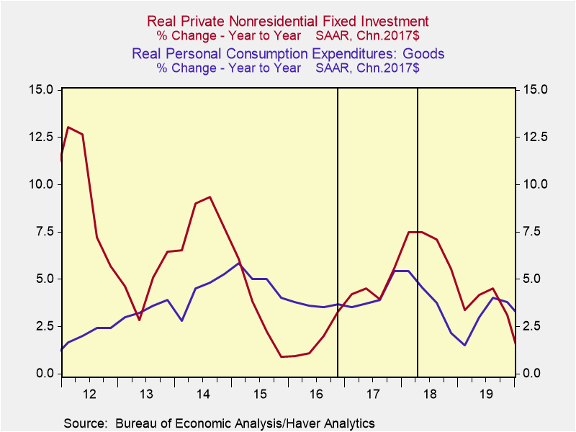

The thrust toward deregulation combined with expectations of tax cuts generated a significant rise in business confidence, business investment (chart 1), and real GDP. The favorable economic conditions continued into 2018.

Chart 1. US investment and consumption

A survey conducted by the National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB) indicated that concerns about government regulations fell sharply from levels recorded during the Obama administration. Anecdotal evidence suggested that businesses were responding to the general perception of a less-burdensome regulatory environment as well as specific changes in regulations that directly benefited them. The rise in business investment spending involved strong gains in information equipment and technology as well as industrial and transportation equipment. Consumer spending also jumped, presumably in response to anticipated tax cuts. Measured fourth quarter to fourth quarter, real GDP growth accelerated from a 2.1 percent average in 2015–16 to 3 percent in 2017.

The imposition of tariffs beginning in mid-2018 undercut business confidence and materially slowed growth of business investment and consumption that reversed the economic momentum. Trump’s initial tariffs, which were imposed by executive order under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which focused on imports that “threaten to impair national security,” involved tariffs of 25 percent on all steel imports and 10 percent on aluminum applied to all imports except those from Canada and Mexico. Trump frequently threatened higher and expanded tariffs, and actual tariffs were frequently modified.

In summer 2018, additional tariffs between 10 percent and 25 percent were extended to imports from China and select other nations under Section 301, which gave authority to the Office of the US Trade Representative to assess tariffs if the policies or practices of a foreign country are “unreasonable or discriminatory and burdens or restricts US commerce.” China retaliated with its own tariffs on imports from the United States, and other nations also retaliated with tariffs.

In direct response, the healthy rise in international trade volumes flattened, and both US imports and exports fell. US imports of consumer goods and autos fell with a lag, while declines in imports of industrial materials and capital goods were more pronounced. US exports of industrial materials and capital goods also fell. The tariffs had a decidedly negative impact on business, as corporate profits flattened. Dividend growth continued but corporate cash flows declined. The 2017 tax cuts reduced corporate tax rates, but a one-time repatriation tax on accumulated foreign earnings cut into corporate cash flows (the government recorded it as a capital transfer from business to the federal government).

Tariffs were disruptive

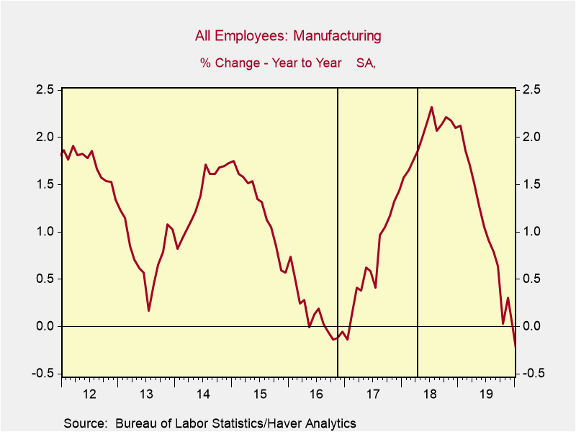

The tariffs did not achieve Trump’s stated objective of shifting production and jobs back to the United States. Nor did the tariffs reduce the trade deficit—it widened. There was some anecdotal evidence of US companies moving some production facilities and people back home, but the net impact was insignificant. Employment in manufacturing, which had benefited from the deregulations and tax cuts, was reversed by the tariffs (chart 2). The tariffs clearly disrupted businesses global supply chains and illustrate the costs of policies that violate the law of comparative advantage. Businesses have expressed the difficulties they face in adjusting their production processes that rely less on foreign inputs, frequently at higher costs.

Chart 2. Employment in manufacturing

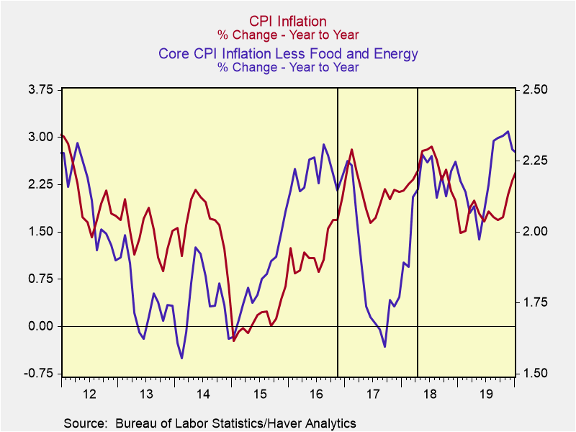

The tariffs’ impact on inflation is also noteworthy. US CPI inflation and core CPI inflation (which excludes food and energy) actually receded after the imposition of tariffs (chart 3). Even though the tariffs raised the business costs of US importers, the deceleration of inflation presumably reflected the slowing US aggregate demand. The price indexes of both imports and exports fell after the tariffs, presumably reflecting the global slump in industrial production that lowered the demand for industrial materials and capital goods.

Chart 3. CPI inflation and core CPI inflation

The Trump economy, round two

While the basic outlines of Trump’s proposals allow the weighing of the pluses and minuses of the package’s economic impact, the lack of details prevents a thorough assessment. The tariffs would harm economic performance and have a one-time impact on the general price level. Extending the tax cuts would lift expected after-tax rates of return, also a positive, but they would not provide the same degree of stimulus as actual tax cuts. Deregulation would be a clear positive, although difficult to measure. Improving the efficiency of government operations would also be a positive, even if government deficit spending is not cut. The massive deportation of immigrants poses a negative risk, although it depends on the extent to which Trump follows through on his campaign rhetoric.

Tariffs: Trump has proposed 10 percent across-the-board tariffs on all imports and a 60 percent tariff on imports from China. He views tariffs as a cleaner and more effective policy than imposing sanctions in a world of unfriendly actors. Tariffs are basically taxes on imported goods and services, which raise the operating costs of importing businesses. History shows that businesses raise product prices and largely pass on the costs to their customers.

Currently, US imports total $4.1 trillion—$3.3 trillion in goods and $0.8 trillion annually in services. Approximately $400 billion of the imports are now from China, down from over $500 billion. US imports of electronics, electrical equipment, and industrial machinery and supplies from China exceed US imports of consumer goods. A simplistic 10 percent tariff on all global imports, assuming no responses, would generate roughly $410 billion in revenues. An additional 50 percent tariff on imports from China (so total tariffs on Chinese imports are 60 percent) would raise an additional $200 billion, for a total increase in revenues from tariffs of $610 billion. This magnitude nearly equals total current corporate taxes and is 16 percent of total profits, suggesting that most likely Trump proposed across-the-board tariffs as an initial strategic negotiable lever, and that ultimately the tariffs would be imposed more selectively. This was the case in Trump’s first term.

In sharp contrast to when Trump assessed tariffs in 2018, global economies, particularly in Europe and China, are weak and diplomatic relations are strained. The tariffs would come at a bad time for China and Europe as they face very soft domestic economies and rely heavily on exports. This increases their risks of aggressive retaliations.

Facing domestic weakness, China has ramped up exports of manufactured goods, most prominently electric vehicles (EVs). Global governments and consumers are pushing back. Canada and Europe have retaliated with high tariffs on imports of China’s EVs.

Europe’s economy is significantly underperforming, with anemic growth, hampered by stifling regulations and higher taxes and very high energy costs stemming from various climate initiatives and regulations that bar efficient and reliable energy production. Germany is now a drag on European economic performance. Germany and Europe as a whole rely heavily on exports to the United States; approximately 17 percent of Europe’s non-EU exports go to the United States.

Extending tax cuts: The key components of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 that affect individual taxpayers, including lower tax rates, increased standard deductions, increased child care credits, the cap on the SALT (state and local tax) deductions, increased AMT (alternative minimum tax) minimum, and a doubling of the estate tax exemption, are due to expire at the end of 2025. (Under current law, the cut in corporate tax rates to 21 percent from 28 percent does not expire.) The Congressional Budget Office estimates that extending the tax cuts will increase deficits by $4.5 trillion over a ten-year budget projection period, compared to current law under which they expire. Trump has also proposed eliminating taxes on Social Security benefits and income from tips and increasing the refundable child care credit, all of which would add further to deficits and debt.

Although Republicans control both the House of Representatives and the Senate and will generally be sympathetic to extending the tax cuts, some members are concerned about already-high deficits and are unlikely to rubber-stamp Trump’s proposals. Opposition is likely in the House Ways and Means Committee, which must originate and approve all tax legislation, and in the Senate Finance Committee, which operates as the fiscal gatekeeper in the Senate. With virtually all Democrats expected to oppose the tax legislation, a small handful of Republicans may force compromise.

A large portion of the 2017 tax cuts is likely to be extended. Trump’s proposal to enhance the child care credit is likely to be included, but other campaign tax proposals that would increase deficits are unlikely to be enacted. Tax legislation is also likely to include deficit-saving measures such as eliminating or modifying some of the tax credits in the so-called Inflation Reduction Act (like the $7,500 tax credit for purchasing EVs) and the CHIPS Act. In addition, clawbacks of some unspent budget authorizations of those and other fiscal packages including the American Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 will provide budget savings.

There is a possibility that the Trump administration will coordinate with Congress on a large fiscal package that includes higher tariffs whose estimated revenues would provide an offset to the deficit increases of extending the tax cuts. By including the revenues from tariffs plus other deficit-saving provisions, the result could be a deficit-neutral or even a deficit-reduction package. This would soften some concerns but would likely generate a battle over dynamic budget scorekeeping and the magnitude of the economic effects of the tariffs. Congressional negotiations that drag out may test Trump’s patience, running the risk that a large fiscal package unravels.

The regulatory environment: Trump has proposed a significant shift toward deregulation that will affect a wide array of economic activities and industries and provide an overall boost to economic growth, lifting confidence, business investment, expansion and hiring. In energy, regulations in oil and gas drilling and pipelines will be eased, and exports of liquefied natural gas may be affected. In the automobile industry, changes in emissions standards may alter production processes and lower costs. In the pharmaceutical sector, changes may streamline FDA approval processes and the costly distribution of drugs. The Biden administration Federal Trade Commission’s general tilt against mergers of large companies will be eased, which may alter the structures of select industrial sectors, encouraging merger and acquisition activities. In housing, regulations that have constrained construction and contributed to housing shortages will be eased. In the financial sector, excessive regulations and compliance requirements affecting traditional consumer and commercial banking and capital market activities will be lessened. The roles and activities of Fannie and Freddie in housing finance may be reviewed and modified, although that would be an ambitious task. An easing of labor regulations would improve both labor supply and demand, benefiting workers and businesses.

Measuring the macroeconomic benefits of deregulation is difficult, and caution is appropriate. Many regulations are entrenched and complex, and prior attempts to eliminate or modify regulations have run into political and legal opposition. Still, dialing back overzealous regulations would set the tone and be positive.

Improving government efficiency: Trump has established a high-profile task force to improve government efficiencies and eliminate bureaucratic redundancies. Such initiatives potentially would generate sizable benefits, but Trump’s statement that the task force will reduce budget deficits by trillions of dollars is misleading. Significant cuts to deficits require changing the benefit structures of the entitlement programs, including Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and the SNAP program, requiring fiscal legislation that would involve Congress.

A more productive approach would be to establish two separate task forces, one that addresses the government’s inefficiencies and considers ways to streamline bureaucracies, and a separate national commission to study and recommend programmatic changes that would reduce deficit spending.

Reducing deficit spending: The persistent deficits and mounting debt are attributable to growing spending for the entitlement programs and rising net interest costs, which have been boosted by the normalization of interest rates after years of negative real rates. While tax receipts have remained at about 17.5 percent of GDP, government outlays have risen to over 23 percent of GDP. The persistent, dramatic increases in spending on entitlements reflects their compounding growth stemming from a combination of inflation indexation—either explicitly in the case of Social Security, other government pensions, and the SNAP program, or the effective inflation indexation of the benefit structures of Medicare and Medicaid—and the aging of the population and the expansion of eligibility of programs like Social Security’s Disability Program.

Again, a caution: government spending programs are well intended and all have beneficiaries and advocates. Entitlement programs have been enhanced in ways that added complexity and expense. Reform requires wise programmatic changes that are both efficient and fair. President Obama created the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, a bipartisan effort co-chaired by Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles, and then absolutely ignored their thoughtful recommendations. Meaningful longer-run deficit reduction requires strategic thinking by fiscal leaders willing to take unpopular steps. Such political leaders are in short supply.

Immigration: Trump’s proposal to deport a massive number of immigrants poses economic risks. However, campaign rhetoric will meet difficult realities, and the actual number of immigrants deported is unlikely to be “massive,” and most likely the macroeconomic impacts will not be nearly as large as pessimists’ warnings.

Immigrants, whether documented or undocumented, on average contribute positively to the economy, taking jobs, earning wages, and spending, and over time lift average labor productivity. The United States welcomes more immigrants than any other country and also deports a sizable number—an estimated 2.5 million deported during the Obama administration and 1.5 million during the Biden presidency. A sizable portion of the immigrants since 2020 are undocumented, and a significant portion are being subsidized by federal, state, and local governments, but the total costs are unknown. The logistics, costs, and potential legal barriers of deporting immigrants pose obstacles, and these realities will likely influence Trump’s deportation initiative.